This fall, our series in 1 Corinthians has focused much of our attention on the spiritual gifts. To that end, we’ve enjoyed hosting a workshop on the Spiritual Gifts and releasing a Park Church Music single by Becca Griffis.

These shared efforts have shared artwork: an image of a building under construction with a “murmur” of birds flying overhead. The intended meaning is simple: in 1 Corinthians 14:12, we who are “eager for manifestations of the Spirit” are charged by Paul to “strive to excel in building up the church.” Likewise, in John 3:8, Jesus tells us, “The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.”

Though our individual lives feel much smaller, the Church in whole is not. How grand is the scope of what the Spirit is building up? In the same way, though we can’t visualize the wind, how do God’s people move like a flock of birds, born of One who works even higher? However, as with all artwork, this is just one interpretation. What does it make you think?

Our artwork for this Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday, Good Friday, and Easter is adapted from a 2021 series by Noel Shiveley for Park Church (also including Advent and Christmas Eve).

About the Artist

Noel Shiveley was born in Pasadena, CA. He first started sharing his graphic design work on Instagram in 2012 under @noeltheartist. His account has become a favorite to many, using graphic design to blend fun social commentary, Gospel snippets, random illustrations, and his professional portfolio. This is how we found him for this project! Noel lives with his wife Bethany in Colorado Springs where he serves as Worship Director for YWAM Colorado Springs.

What does the artwork mean?

In each piece, a wide “landscape” is pictured. From the outside edges in, rolling hills, jagged deserts, or the ethereal cosmos center a symbolic item and a celestial body. The symbols each focus on life as it is traditionally considered in its liturgical season. For example, Ash Wednesday depicts ashes blown from a censer (life as temporary, fleeting; Psalm 90:3, 10), while Palm Sunday shows a budding tree in front of a gate cracked open (new life imminently coming; Mark 13:28).

What has changed for 2023?

To see Noel’s artwork in a new way, we’re applying a traditional liturgical color and a contrasting thematic color to each of the landscapes. For example, the traditional color for the season of Lent is purple, and a common reminder from the season is that “All are from the dust, and to dust all return” (Ecclesiastes 3:20).

Current 2023 Pieces

Ash Wednesday

Palm Sunday

Good Friday

Easter

2021 Pieces

Palm Sunday

Good Friday

Easter

Advent

Christmas Eve

Artwork is another way for us to imagine the realities of Christ’s kingdom. When art works as devotion—training us to see with the eyes of faith in new ways—it can grow our imagination, even in the theological sense. Our Advent Series this year is focused on the Second Coming of Christ. As shared on our Advent page, though now often neglected or misunderstood, the promise of Jesus’ return remains vital.

My name is JD, and I work as Director of Communication and Art at Park Church. As I considered supporting this series visually, the biggest felt need I identified was a cultural lack of imagination around the Second Coming. This isn’t to say that the ideas that come into our minds when we hear “The Second Coming” are boring, but probably just too infrequent! The “lack of imagination” I’m describing is simply a lack of imagining.

In response, I created three pieces for the series by “compositing” several photos from a handful of international photographers and artists, each credited below. I’m excited to explain these to you! I pray your imagination is put to work both as you view these and as you consider to daydream with me about the return of Jesus Christ.

Banners:

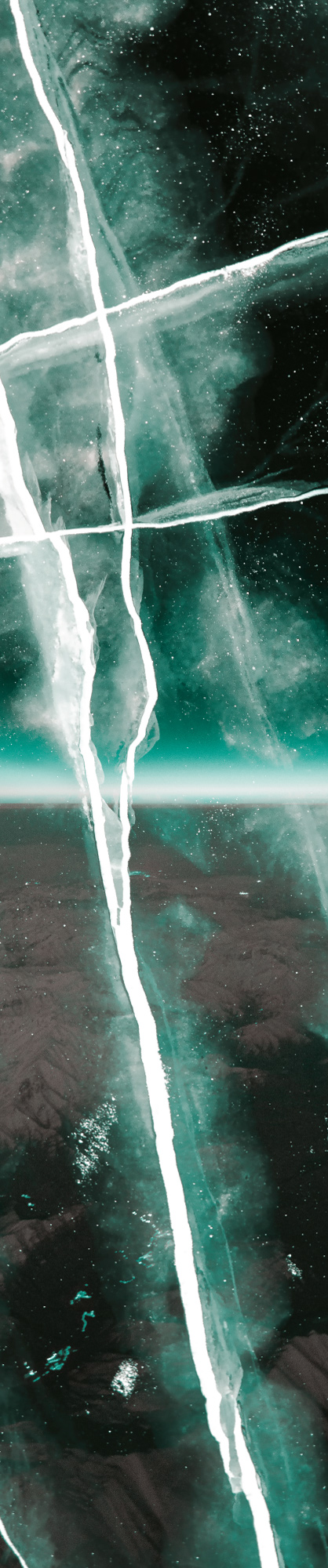

Left Banner:

Imagining the moment of His return, a dark horizon is shown with dawn approaching. A few city lights are visible, and something like lightning crosses over everything. This references Jesus’ words about how well we’re going to know it when He returns! (Matthew 24:27) While some parts of the landscape pictured show city lights, much of the earth’s surface is dark. One way to “read” this contrast is as an illustration of Jesus’ parable in Matthew 25: wise and foolish members of a bridal party with some keeping watch at all hours to meet the bridegroom.

The aerial landscape photo is from Daniel Olah, taken over Istanbul, Turkey. The “lightning” image is a photograph of ice on a lake near Miass, Russia, taken by Daniil Silantev.

Right Banner:

Imagining just a sliver of the grandiose New Jerusalem (Revelation 21:9–27), tall white buildings with unrealistically tall chapel-like windows are shown, covered in either a) some kind of glory cloud (Hebrews 12:18–24), or b) some kind of bridal veil (Revelation 21:2).

The photo of the buildings (actual earth buildings!) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia is by Bady Abbas. The veil/cloud image comes from an aerial photo of an Arctic iceberg, taken by the incredible Annie Spratt.

Central Image:

Perhaps conveying more tension than glory, a condensation-laden mirror is shown sitting on a sturdy sprig of baby’s breath. Over the top is a fiery glare to suggest some of the weight of 2 Peter 3. A few things are intended to be communicated here: First, we are encouraged in 1 Corinthians 13:9–12 that “now we see as in a mirror dimly, but then face to face…”. Second, Romans 8:19 teaches us that the “the whole creation waits…” Here a strong-enough member of creation—the sprig of flowers, is shown holding the weight of this unclear image. Third, and maybe too overtly, the flowers shown are literally “baby’s breath.” This is the only nod to the first coming of Christ, an astounding cosmic moment when God took a first breath.

Lastly, though much smaller than a tree, the plant shown resembles the shape and branches of a much larger tree. Three meanings can be extracted here if you’re willing! First, Jesus tells us that the kingdom is like a mustard seed planted (Matthew 13:31–32). This Jesus embodied, coming first as a humble Servant to be literally planted in the ground, growing a great kingdom of Servants in the Church age, and later coming back bodily as the only authority—King of the Kingdom final. In the shape of this sprig of baby’s breath, shown under the weight of the age, a full tree is promised in a way. Secondly, one of our greatest hopes is a restoration of access to the the tree of life (Genesis 3:22, Revelation 22:2) and the mystery of immortality. Thirdly, and with much less theological effort, a better vision for a Christmas tree is proposed. Please forgive that.

The baby’s breath is an adapted photo, also by Annie Spratt. The glare is from a photo by Ruan Richard Rodrigues. The condensation is from a photo by Aaron Jean.

The artwork for our ongoing Matthew series is by Lane Geurkink, a Denver mixed-media artist and Park Church alumni.

Why the upside down crown?

The more time we spend considering the kingdom Jesus came to establish, the more it contrasts with the kingdoms around us. In this Kingdom of Heaven, the outcasts are welcomed, the humble are honored, enemies are loved, the poor are esteemed, strangers are befriended, and the guilty are forgiven. Its King is enthroned on a cross, His victory comes through His death, and His death gives life to the world. In short, it’s “upside-down”.

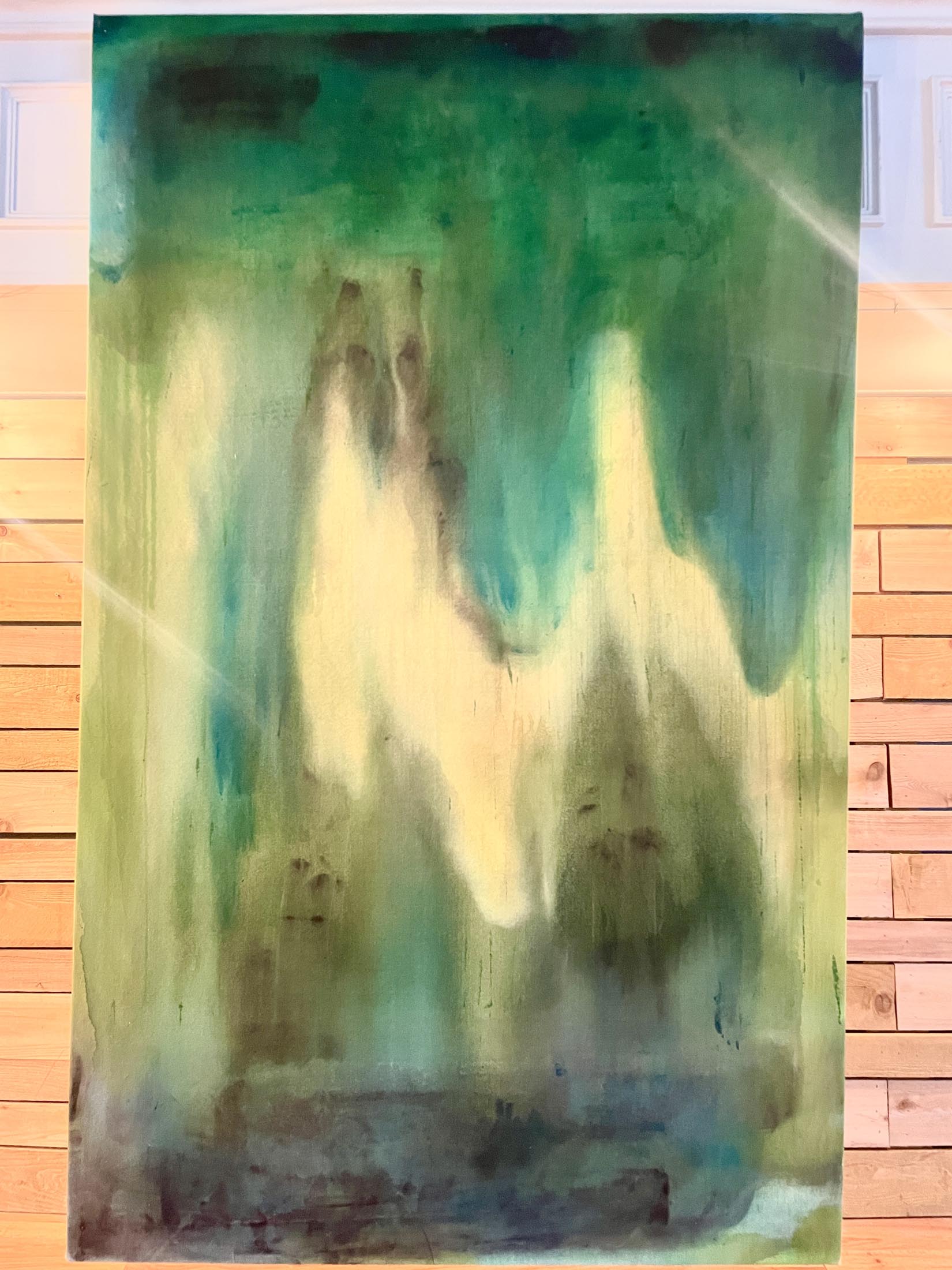

To illustrate this concept, we asked Lane to paint a series of upside-down crowns. A different crown has represented each semester or “part” of the series, of which there have now been six. What started as a simple, thin crown in Matthew Part I (Spring 2020) has grown more intense and full for each new Part Starting in Part V (Spring 2022), we began to combine or “composite” Lane’s original crown paintings to keep the crowns growing, all the while seeking to illustrate that Jesus plan continues to be beyond and other than our expectations:

What do the banners mean?

For Matthew Parts I–IV, a large banner was displayed on each side of the front of the sanctuary. Lane created these banners by dying sheets of natural canvas with things like rust and indigo plants. Inspired by the abstract work of Mark Rothko, the giant “color fields” are a space to see and feel different things as one walks with Jesus through this Gospel: warmth, cold, cheer, and even confusion. These pieces stand in significant contrast to some of our past sermon series artworks where meanings have been more direct and implied. What did you see in these banners?

And the piece in the gallery?

For each of the 93 Sundays we’ve spent in Matthew to-date, we’ve displayed a “central” piece by Lane in the gallery. An upside-down crown is pictured off-center on a massive natural canvas, marbled with natural indigo dye. Like many of Jesus’ teachings, a complexity and a simplicity are both accessible, but the upside-down nature of His kingdom clearly stands out.

What are the new pieces on stage for Part VI?

We’re in chapter 20 as this article is written, and Part VI is finding us headed to Jerusalem with Jesus for what will eventually be His death and resurrection. Through the end of our Matthew series (Part IX?), the “metanarrative” of Scripture and all of history is reaching its climax in Christ.

To place ourselves within this big picture, we are re-displaying four of Lane’s paintings, originally done for a Park Church Bread and Wine event in 2014. The pieces retell this grand arc of Scripture: (1) Creation, (2) Fall, (3) Redemption, and (4) Glorification.

We are so grateful to Lane for her incredible work on these seven pieces and several crown paintings. Thank you for challenging us to disciple our eyes as we disciple our hearts.

Photo Credits

Photos of banners and gallery piece by Melanie Fenwick. Photos of “metanarrative” pieces are from an iPhone and not by Melanie (sorry Lane!).

Our artwork for Advent and Christmas Eve this year is by Noel Shiveley. These pieces complete the series Noel has done for us this year within the church calendar (also including Lent, Palm Sunday, Good Friday, and Easter—see below). But what does the artwork mean?

the series as a whole

In each piece, including Advent and Christmas Eve, a wide “landscape” is pictured. From the outside edges in, rolling hills, jagged deserts, or the ethereal cosmos center a symbolic item and a celestial body. The symbols each focus on life as it is traditionally considered in its liturgical season. For example, Ash Wednesday depicts ashes blown from a censer (life as temporary, fleeting; Psalm 90:3, 10), while Palm Sunday shows a budding tree in front of a gate cracked open (new life imminently coming; Mark 13:28).

“the weary world rejoices”

Our series for Advent this year has been “The Weary World Rejoices.” Our intent is first to make space in our hearts to feel the tension and dissonance of our weary world (this will be easier for some than for others) while also looking to Jesus as the one who took on flesh to secure the promise of a better future here: a future where the disillusioned can have hope, where the divided can find peace, where the suffering can experience joy, and where the self-centered and outraged can know love.

Advent

A shadowed world is centered low, hung in a mostly-empty cosmos. Space is clouded, and the space dust is somewhat serpentine, covering stars. Sources of light are partially obscured, but clearly coming—a dark world, but not for much longer (John 1: 9). As the four weeks of Advent progress, the artwork depicted on our bulletins and screens changes to show a rising moon and star. The symbolism for life is somewhat direct: the world is conflicted and gloomed, and all life therein waits for the light. Even more directly, the Bethlehem star is depicted. Though it was a symbol in the sky to guide those seeking to meet Jesus, it was not a “symbol” in that it was a real celestial event—baffling the experts then as it may even now. Such was the first coming of Jesus.

Christmas eve

A depiction of Bethlehem is shown under complex light—the tops of towers are lit; the streets are dark. Feelings of sunrise are suggested (one who considers the last art piece might say, “at last!”), but the barren desert hills around still depict a cold nighttime. John writes that “the true light which gives life to everyone was coming into the world,” but also that “the light shines in the darkness…” (John 1:4–5). As we now know, “the darkness has not overcome it,” but what tension on that night! Why such squalor for this King? Who is this family? Did these shepherds really get a personal invitation from angels?

The artist

Noel Shiveley was born in Pasadena, CA. He first started sharing his graphic design work on Instagram in 2012 under @noeltheartist. This account is now a favorite to many, using his design to blend fun social commentary, Gospel snippets, random illustrations, and his professional portfolio. This is how we found him for this project! Noel now lives with his wife Bethany in Colorado Springs where Noel serves as Worship Director for YWAM Colorado Springs.

The series to date

Click an image to enlarge. All images Copyright Park Church 2020–2021.

Ash Wednesday

Palm Sunday

Good Friday

Easter

Advent

Christmas Eve

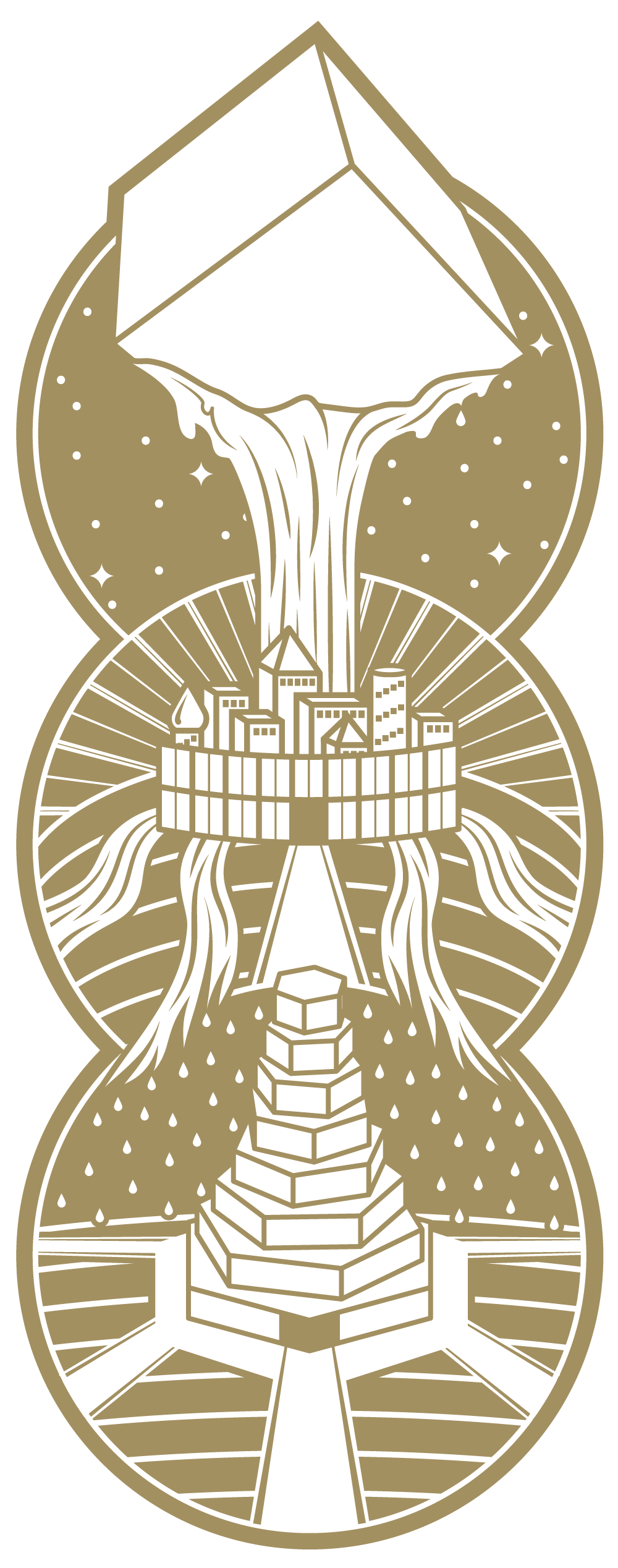

Our artwork for the ongoing Mission of God course is an illustration by Bruce Butler. Three overlapping circles contain depictions of three cities (from top to bottom): the heavenly Jerusalem as described in Revelation 21, the “City on a Hill” as described in Matthew 5, and the Tower of Babel as described in Genesis 11. The cities are connected by a depiction of the River of Life (Revelation 22). This illustration reads in two directions—from top to bottom and from bottom to top.

Read from bottom to top, the humanity-wide quest to live a meaningful life in a broken world starts by default at the Tower of Babel. If we are not working towards God’s mission, the next mission we pursue is our own.

Although we may be able to do incredible things as individuals or as a culture, the charge to mankind was to image God in the world, not simply to image ourselves. In grace to us, God breaks up our godless work. Jesus comes with a new city in mind, a “city on a hill” that “cannot be hidden.” We are invited to be members of this city, displaying Jesus’ upside-down kingdom in the sight of all people. In ironic contrast to Babel (a city that wanted its works to be widely visible but was then abandoned at God’s decree), Jesus expressly charges the city on a hill to have its good works seen! However, it is for the glory of “your Father who is in heaven.” Lastly, we are invited higher again through Jesus’ vision to John of the heavenly Jerusalem, a “cube of meeting” that represents the holy of holies in the temple. The city on a hill of our present age ultimately becomes the heavenly Jerusalem, where heaven and earth finally meet in fullness.

Read from bottom to top, the humanity-wide quest to live a meaningful life in a broken world starts by default at the Tower of Babel. If we are not working towards God’s mission, the next mission we pursue is our own.

Although we may be able to do incredible things as individuals or as a culture, the charge to mankind was to image God in the world, not simply to image ourselves. In grace to us, God breaks up our godless work. Jesus comes with a new city in mind, a “city on a hill” that “cannot be hidden.” We are invited to be members of this city, displaying Jesus’ upside-down kingdom in the sight of all people. In ironic contrast to Babel (a city that wanted its works to be widely visible but was then abandoned at God’s decree), Jesus expressly charges the city on a hill to have its good works seen! However, it is for the glory of “your Father who is in heaven.” Lastly, we are invited higher again through Jesus’ vision to John of the heavenly Jerusalem, a “cube of meeting” that represents the holy of holies in the temple. The city on a hill of our present age ultimately becomes the heavenly Jerusalem, where heaven and earth finally meet in fullness.

Read from top-to-bottom, the River of Life flows from the heavenly Jerusalem down onto the City on a Hill. This city acts as a watershed, and a “preview” of this river is precipitated to the world through it. Two things are intended in this illustration. First, God abundantly provides from heaven for those who seek to be on His mission. For example, we have the Holy Spirit, we have His incredible promises through His Word, and we are on mission within a community and inspired by the faithful before us. Second, the world that is not yet on mission with God receives a sort of gracious, River of Life “rain” by the faithfulness of God’s people as we seek to image Him. Though far different than drinking from the river, feeling its mist makes the human heart yearn for more. “Therefore, we are ambassadors… God making His appeal…” (2 Corinthians 5:20).

Lastly, the circles overlap as a way to illustrate that we are truly “residents” of all three cities. We often pursue our own missions like the people of Babel, and the “rain” of the River of Life is for our coming-to. We likewise often join Jesus in His mission and demonstrate Him to the world, empowered by heaven and its King. Ultimately, “we seek the city that is to come” (Hebrews 13:13), to which we belong as a result of Jesus’ work, enjoying Him and His completed mission until we drink straight from the river with all the redeemed.

This is part four in a series on our artwork for “Echoes of a Voice,” our series for Advent 2020. If you haven’t read the intro to the series, start there first! You don’t need to read each post in order, but here is post one, post two, and post three if you haven’t seen them.

Replay the “Delight in Beauty” Service

Creation is filled with beauty. The beauty all around us sings of God’s design. God is beautiful. Jesus is beautiful. Of course we should seek after beauty! But what are we inclined to do with our beauty cravings? Is it easy to satisfy our hearts (prone to wander as they are) with the notion that all beauty is meant to direct our gaze upward toward our maker? Cheap “beauties” surround us, and to make matters worse, our culture tends to tell us things that draw us inward: “You are what’s most beautiful—if people would just stop to appreciate you!”

In this fourth John Forney photograph from his What Remains? series, a flood of cottontails is illuminated. One could easily stop there, enjoying the glow, not fully actualizing the ancient skeleton homes that stalk the background.

While the illuminated cottontails are beautiful and should, by all means, be enjoyed as such, they also give us a good example when it comes to our delight in beauty: the glow comes from light outside of the frame. As David writes in Psalm 16:2, “I say to the LORD, ‘You are my Lord, I have no good apart from You’,” anything abstracted from God cannot be enjoyed in full, but only out-of-context. The skeleton home of our world, which perpetually tries to delight in beauty (or anything) apart from God, serves as a stark reminder: there’s nothing to see if not for the light.

But how that light shines! In Advent, we remember that “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it,” because “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us…”

When we look upon the Lord, in all His splendor and beauty, it brings us truest joy; an unending joy that cannot be taken away. This comes from following the beauty from the illuminated, earthly thing, to the illuminator. The joy and beauty at the end of that path is not dependent on our emotions, our mood, or what beauty we can “feel” (in ourselves or in the world around us). In addition to this being the beauty we were always meant to enjoy, the beauty of God is also what we ourselves were meant to put on display to others.

This is part three in a series on our artwork for “Echoes of a Voice,” our series for Advent 2020. If you haven’t read the intro to the series, start there first! You don’t need to read each post in order, but here is post one and post two if you haven’t seen them.

Replay the “Quest for Spirituality” Service

It is normal for us to search for meaning and purpose through some sort of spirituality. This desire is an echo of God’s voice as we long to know Him, to have faith in Him, and to be in union with Him. We try to find meaning and purpose in our lives. We may try to make sure we’re “good people” by doing the right things. Sometimes we try to be religious or spiritual just to be religious or spiritual.

This third photograph from John Forney’s What Remains? series is from a marble mine in Marble, Colorado. A high ledge is seen in the right hand side of the photo, and on the left hand side the cavern drops steeply, with an entrance/exit tunnel letting light in. If the difference in elevation between the lighter rock shelf and the cave entrance below is not immediately obvious, the texture on the dark wall is worth a second look: a hundred layers of excavation clarify the dizzying difference. So why this photo?

Without Christ in mind, our quest for spirituality progressively reveals something that horrifies us, whether or not we concede to it: it’s a long way up from here. We’re faced with an astounding wall and we have no rope, no ladder, and truly no choice—our innate drive is to get up there, to not stay in the depths. It’s easy to see why. But the light at both the top and the bottom of this cave is the same—an echo from the surface.

The Christian has a drastically different faith than any other religious or spiritual system in the world, and it all boils down what we do at this universally-met “cave wall.” In Christ, God has already done all the work to make us acceptable; to meet us to transcendence beyond ourselves. In Christ, God has showed us clearly that He loves us and has rescued us into His joyful union—without us doing anything. In Christ, though cave is still dark and we know how deep down we are, all we need to do is trust that Jesus completed the work, turn our hearts toward His well-evidenced love, and live in joyful response.

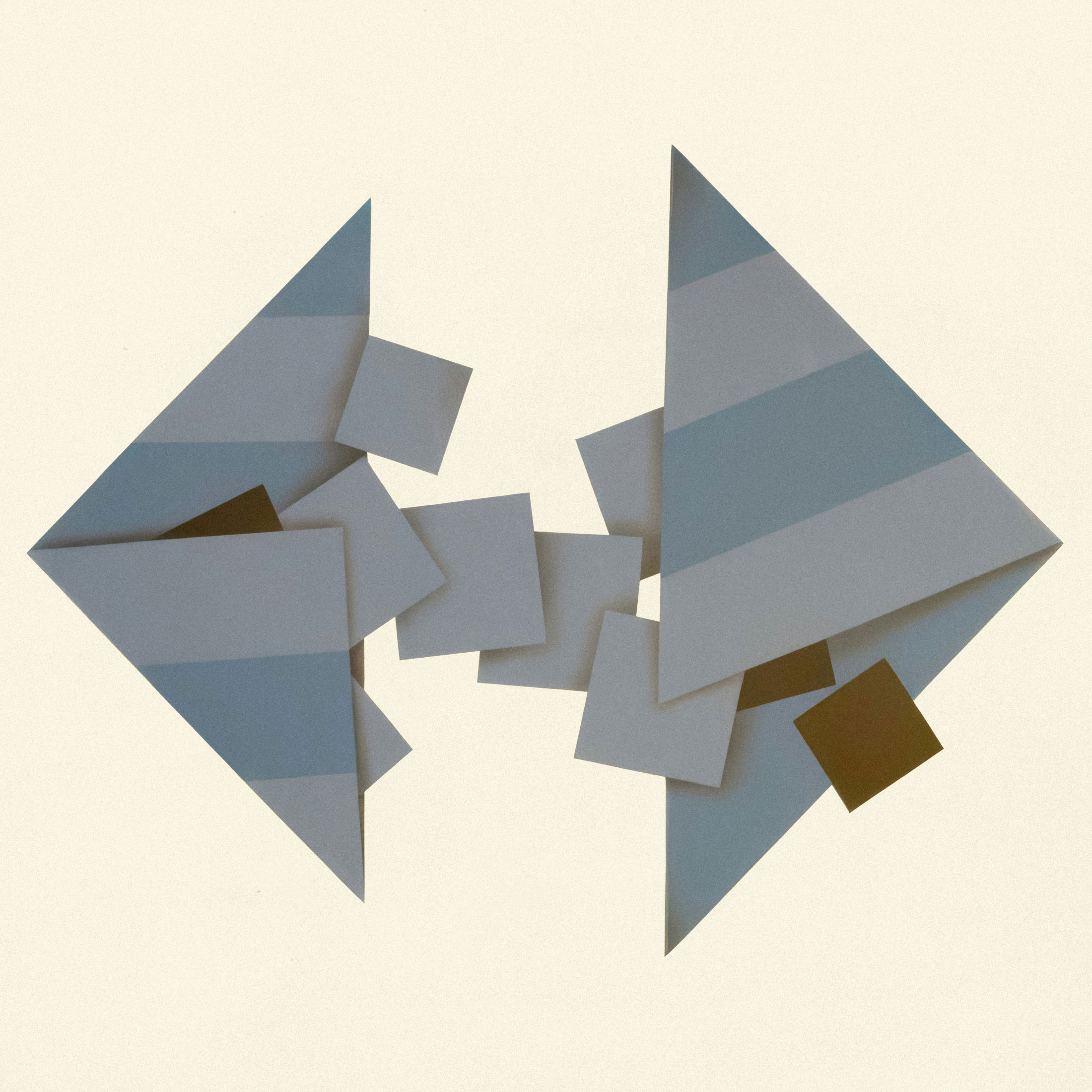

The squares feel as if they move from left to right and create a narrative. Perhaps only one square moves, but we see it pictured in a few “stages” of its journey? The dark square at the beginning (hidden in the fold of the large left triangle) and the dark square at the end (falling out of the larger right triangle) work as bookmarks in a journey: a start and an end. In particular, we may see a movement reminiscent of Genesis 3:19—from dust to dust; a falling like gravity.

The squares feel as if they move from left to right and create a narrative. Perhaps only one square moves, but we see it pictured in a few “stages” of its journey? The dark square at the beginning (hidden in the fold of the large left triangle) and the dark square at the end (falling out of the larger right triangle) work as bookmarks in a journey: a start and an end. In particular, we may see a movement reminiscent of Genesis 3:19—from dust to dust; a falling like gravity. Though the shapes furthest back in this composition are dark (perhaps representing original “dust,” as referenced in the Ash Wednesday piece), there is a lighter foreground, appearing as a sort of sash over the purple rectangle (Lent is traditionally represented with the color purple). Taken altogether, this purple rectangle can illustrate the tension we feel in this season: mortality and sin is right behind us, but in Christ we are truly wrapped in His righteousness and life. Furthermore, in the image, the black shape is separated from the purple rectangle by this white sash—just as we are ultimately separated from our sin and death. The question of “how is any of that possible?” is appropriately felt!

Though the shapes furthest back in this composition are dark (perhaps representing original “dust,” as referenced in the Ash Wednesday piece), there is a lighter foreground, appearing as a sort of sash over the purple rectangle (Lent is traditionally represented with the color purple). Taken altogether, this purple rectangle can illustrate the tension we feel in this season: mortality and sin is right behind us, but in Christ we are truly wrapped in His righteousness and life. Furthermore, in the image, the black shape is separated from the purple rectangle by this white sash—just as we are ultimately separated from our sin and death. The question of “how is any of that possible?” is appropriately felt! Bright yellow shouts of happiness are present, but as in the previous piece for Lent, dark shapes are furthest back in our image. The irony of Palm Sunday is clear—those who know the whole story can rejoice with a “Hosanna!” while knowing that “Crucify Him!” can come from the same place. We say with David “Unite my heart to fear Your name!” (Psalm 86:11). This art piece also shows a white shape entwined above, between, and below the other shapes. As in our piece for Lent, I see this white “path” representing the presence and foreknowledge of Christ in all of the happenings of Holy Week (and how it plays out in our hearts today).

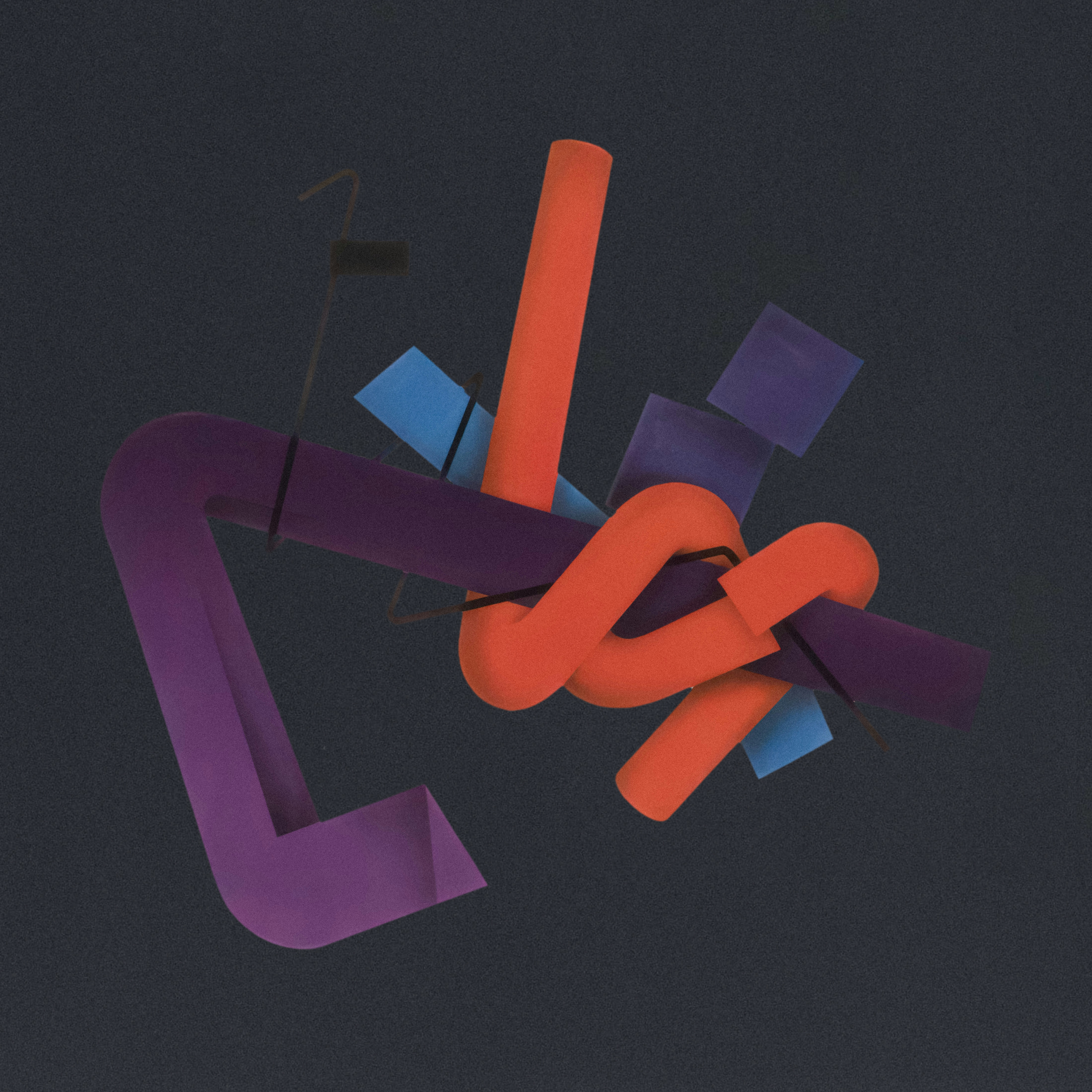

Bright yellow shouts of happiness are present, but as in the previous piece for Lent, dark shapes are furthest back in our image. The irony of Palm Sunday is clear—those who know the whole story can rejoice with a “Hosanna!” while knowing that “Crucify Him!” can come from the same place. We say with David “Unite my heart to fear Your name!” (Psalm 86:11). This art piece also shows a white shape entwined above, between, and below the other shapes. As in our piece for Lent, I see this white “path” representing the presence and foreknowledge of Christ in all of the happenings of Holy Week (and how it plays out in our hearts today). As we get to this piece, all instances of light and warmth are gone. The black present in the other pieces is now the entire background. The white shape and/or path from the previous pieces has turned purple, and is wrapped in red and black serpentine forms. The white turned purple illustrates the royalty of Christ in His death (his upside-down throne). The red and back illustrate the hatred, the sin, and curses that fell on Him in this moment. It’s an entangling, suffocating mess, but the shape representing Jesus is shown as larger as the other shapes, extending well past them and even turning to “see” them. His sovereignty is unaffected.

As we get to this piece, all instances of light and warmth are gone. The black present in the other pieces is now the entire background. The white shape and/or path from the previous pieces has turned purple, and is wrapped in red and black serpentine forms. The white turned purple illustrates the royalty of Christ in His death (his upside-down throne). The red and back illustrate the hatred, the sin, and curses that fell on Him in this moment. It’s an entangling, suffocating mess, but the shape representing Jesus is shown as larger as the other shapes, extending well past them and even turning to “see” them. His sovereignty is unaffected. As you view this piece, I challenge you to picture it as “zoomed out” in comparison to the other pieces. Imagine that its scope has to be much larger! Shapes of yellow and black that previously seemed central are now laying small against a massive, layered backdrop that’s bright with the shades of a dawn sky. The white from earlier pieces now wraps around the sky and amongst the shapes on the ground, even supporting the yellow and black shapes. It’s as if the whole “stage” is now visible, and the end is clear.

As you view this piece, I challenge you to picture it as “zoomed out” in comparison to the other pieces. Imagine that its scope has to be much larger! Shapes of yellow and black that previously seemed central are now laying small against a massive, layered backdrop that’s bright with the shades of a dawn sky. The white from earlier pieces now wraps around the sky and amongst the shapes on the ground, even supporting the yellow and black shapes. It’s as if the whole “stage” is now visible, and the end is clear.