Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation

Overview

In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two radically different prophets with a common mission: to confront God's people with the truth about His heart. Jonah runs from God's heart of mercy; Amos runs toward God's heart for justice. Together, these books expose the ways God's people resist His heart and mission, and invite us into deeper alignment with His restorative purposes in the world.

In a culture marked by spiritual apathy, social injustice, political polarization, and self-absorbed living, these prophets speak with timely relevance for our lives in Denver today.

Jonah: God's Reluctant Prophet of Mercy

Jonah is a story-driven prophetic book centered around a reluctant prophet who is called to preach repentance to Israel’s enemies in Nineveh. Jonah refuses, not out of fear, but because he knows God is merciful—and he doesn't want Nineveh to receive that mercy. God relentlessly pursues both Jonah and the Ninevites, extending His compassion to rebels—insiders and outsiders alike.

Key Themes:

- God’s heart of mercy for all nations

- The danger of self-righteousness and tribalism

- God's pursuit of our hearts, not just our obedience

- The irony that “outsiders” often respond more faithfully than God’s own people

Amos: God's Courageous Prophet of Justice

Amos is a shepherd from the south (Judah) sent to confront the elite in the northern kingdom of Israel. He denounces empty religious rituals, economic injustice, and societal complacency. Amos reveals how deeply God cares about righteousness, justice, and covenant faithfulness—and how His people can no longer separate worship from daily ethics.

Key Themes:

- God’s justice and judgment

- The inseparable connection between worship and justice

- The danger of religious complacency and materialism

- God's heart for the poor, the oppressed, and the marginalized

Sermons

Amos 9

Sunday, November 23, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Amos 8

Sunday, November 16, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Amos 7

Sunday, November 9, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Amos 6

Sunday, November 2, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Amos 5

Sunday, October 26, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Amos 3–4

Sunday, October 19, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Amos 1–2

Sunday, October 12, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Good News for the City (Luke 7:36–50)

Sunday, October 5, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Jonah 4

Sunday, September 28, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Jonah 3

Sunday, September 21, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Jonah 2

Sunday, September 14, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Jonah 1

Sunday, September 7, 2025

Jump to SermonsJump to Artwork Explanation Overview In this series, we’ll walk through the prophetic books of Jonah and Amos—two […]

See More ›Behind the Art: Drew Button

Intro

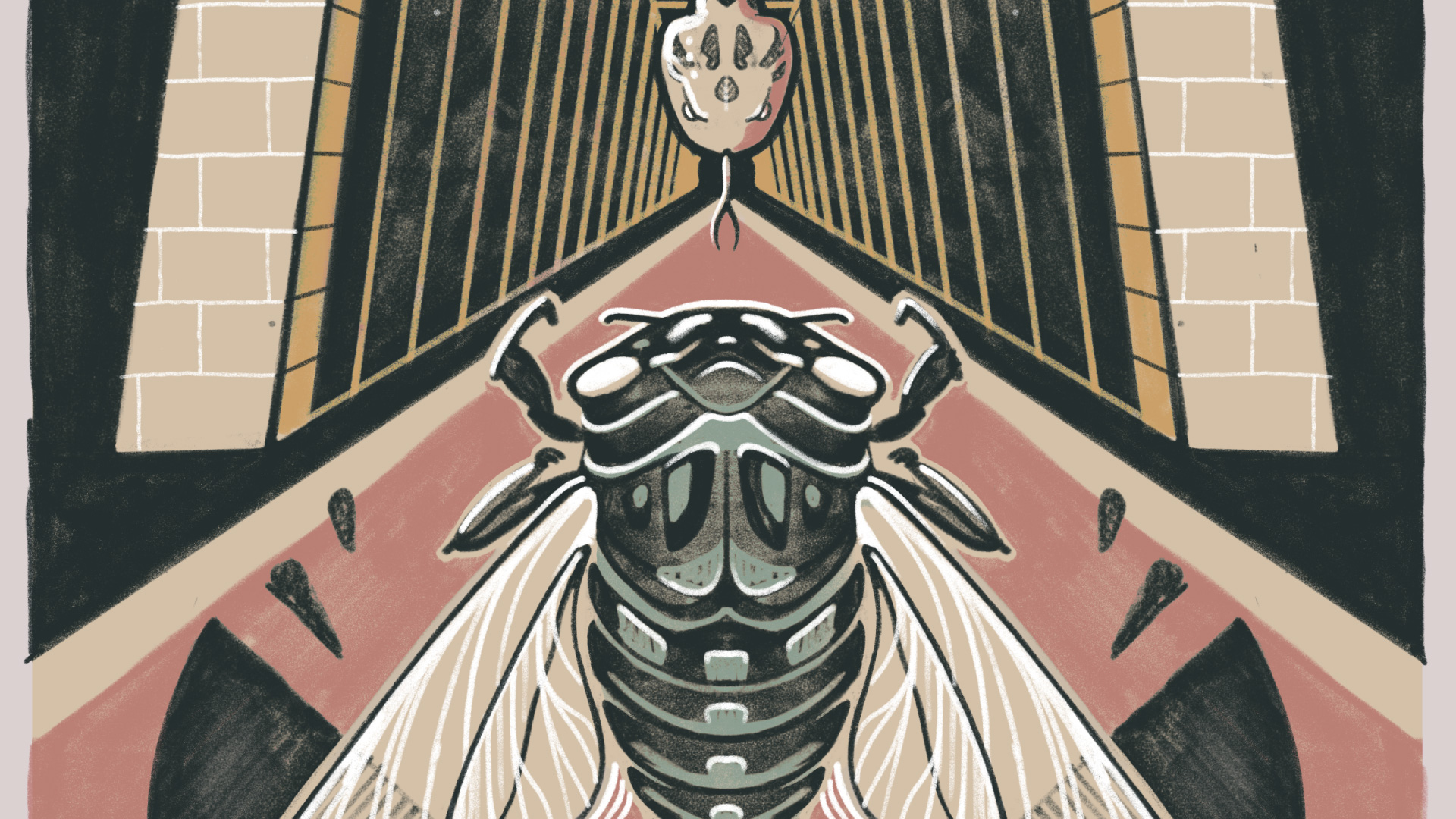

Jonah and Amos are rich, multilayered texts, each offering us a suite of different themes and, therefore, visual images to explore them with. Images help us engage our imaginations, pushing up against our inclination to over-analyze a text that risks simplifying or flattening it into something less than it is meant to be. On the other hand, images can also be freighted with too much of ourselves: our memories and experiences can restrict certain symbols in ways that need stretching. A book like Jonah, for example, can bring with it memories of childhood, and the softened version of the story that is found in children’s books. This story is of course meant for children, but it is also more than that, it is meant to help us grow, surprising us with layers as we dig deeper.

Jonah and Amos are rich, multilayered texts, each offering us a suite of different themes and, therefore, visual images to explore them with. Images help us engage our imaginations, pushing up against our inclination to over-analyze a text that risks simplifying or flattening it into something less than it is meant to be. On the other hand, images can also be freighted with too much of ourselves: our memories and experiences can restrict certain symbols in ways that need stretching. A book like Jonah, for example, can bring with it memories of childhood, and the softened version of the story that is found in children’s books. This story is of course meant for children, but it is also more than that, it is meant to help us grow, surprising us with layers as we dig deeper.

Images aid our contemplation in meaningful ways, acting as multi-layered, visual metaphors. It can be seen as the job of the artist to attempt to create a space that engages the imagination, where the contemplation of Scripture can wash upon us in new ways.

On this Jonah and Amos project, we were excited to work with illustrator and muralist Drew Button. His work has appeared across Denver, and his imagination, attention to detail, and skill are apparent in all he does. I had the joy of sitting down with Drew to talk about this recent project and what not only went into the making of these banners, but also the meaning that was chosen to be sown into the final images.

Q&R

Seth: What went into your process of discovering these images, in the early stages of imagining them?

Drew: In the early stages of design, I had to remain as loose as possible—to avoid getting trapped in familiar motifs associated with the books of Jonah and Amos. I dove head first into both texts, had a Bible study session with you, Seth, and began research to understand the obvious symbols that appear in both texts. I wanted to explore how those more traditional symbols could translate to symbols that we, as Christians in Denver at Park Church, would encounter in our day to day lives in the city or the wilderness. The initial pass at creating the artwork was done with pen on paper in broad, sweeping strokes. This approach was different from the path I take on many other projects in that it didn’t begin in a digital workspace. I find it easy to become stuck in premature refinement and perfectionism in digital drawing because the tools allow you to easily erase, undo or preserve/reevaluate old ideas. Working with a pen is irreversible and only allows your train of thought to move forward (without second-guessing or back-tracking). When imagining these symbols at first, they were fluid and lacked definition or representative form. There are so many layers of meaning in both Jonah and Amos. After the first couple of passes, it is hard to pull any really concise imagery from reading them other than a man on the run, a boat, a storm, or a great fish. Imagine looking down through a deep stack of overhead projector transparencies, each with their own illustration on them—this is how I felt looking down through the layers of Jonah and Amos, trying to identify symbols that I thought my community could connect with, that I could connect with, and that could be truly tied to the stories of each prophet.

Seth:What do images and symbols mean to you as an artist?

Drew: Symbols have been important to me from a young age. Each symbol I found as a young artist always seemed to represent an idea or belief that I felt could bring me strength, a sense of peace, or confidence in the face of adversity. As a young person, I was first exposed to the symbols of the Catholic Church, then Boy Scouts. Friends and mentors in both spaces led me to the epic sagas of The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia. As a result of these symbol-rich immersions, I began drawing my own crests, logos, and coded languages where each marking carried its own meaning and representation of an English letter. I felt inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien's ability to fuse deep meaning with strikingly beautiful objects that existed only in his detailed descriptions of them. Not only were there object symbols, but the characters who carried these objects were themselves viscerally symbolic. All this to say that symbols and characters (animals or people) have the power to reach young minds and individuals across cultures from every different background. They are important communication tools for everyone—to serve almost any purpose we need them to. I’ve realized that I use symbols in my work to convey meaning in a similar way that authors like Tolkien and C.S. Lewis used them; as objects, animals, or characters that represent ideas we are often met with in our real lives.

Drew: Symbols have been important to me from a young age. Each symbol I found as a young artist always seemed to represent an idea or belief that I felt could bring me strength, a sense of peace, or confidence in the face of adversity. As a young person, I was first exposed to the symbols of the Catholic Church, then Boy Scouts. Friends and mentors in both spaces led me to the epic sagas of The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia. As a result of these symbol-rich immersions, I began drawing my own crests, logos, and coded languages where each marking carried its own meaning and representation of an English letter. I felt inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien's ability to fuse deep meaning with strikingly beautiful objects that existed only in his detailed descriptions of them. Not only were there object symbols, but the characters who carried these objects were themselves viscerally symbolic. All this to say that symbols and characters (animals or people) have the power to reach young minds and individuals across cultures from every different background. They are important communication tools for everyone—to serve almost any purpose we need them to. I’ve realized that I use symbols in my work to convey meaning in a similar way that authors like Tolkien and C.S. Lewis used them; as objects, animals, or characters that represent ideas we are often met with in our real lives.

Seth: In what ways are creating and utilizing symbol and image similar or different when you are constructing something for the church versus the larger city outside?

Drew: I wanted these symbols to be relatable mostly to residents of Colorado, whether you’re a newcomer or have grown up in this state or anywhere else in the Great Plains or Rocky Mountain regions. If you take these banners out of the church, onto the sidewalk and hang them from a streetlight on Federal Boulevard, I want the out-of-context viewer to be able to ask themselves, “What is this supposed to mean?” People with different backgrounds would all pull different meanings from the individual elements, including how those elements interact with one another. That said, I wanted there to be clear takeaways: upward movement, downward movement, transformation, a trial or journey, a confrontation, a sudden shift, a beginning, an end. I also wanted there to be symbols that elicit a similar response no matter who you are: a snake, an insect, a peach, roots, a tunnel, a temple. In the church, these animals can be tied to sin, parables, plagues, faithfulness, foundation. On the street, a non-Christian person, might interpret them similarly. For example, the rattlesnake. To someone who has grown up anywhere in the U.S., the rattlesnake in all its species is a fearsome and deadly foe. As Christians and non-Christians alike, we see this as a symbol of something to be avoided at all costs—an encounter with the snake can lead to death. So to answer the question, I created symbols for this project in a similar way that I might create them for another project outside of the church. Rooting the artwork in something you can point to—like history, a text, someone’s personal story, or a brand—usually lands with a larger audience no matter where it’s found.

Let’s break down the symbols

Jonah (left)

Amos (right)

Conclusion

Working with Drew on the Jonah and Amos banners has been a journey of discovery, blending Scripture, symbolism, and visual storytelling. Through these images, the messages of the prophets are made tangible, prompting reflection and engagement from a wide audience. The interplay of local imagery with timeless biblical motifs creates a rich, layered experience—one that invites both contemplation and conversation.