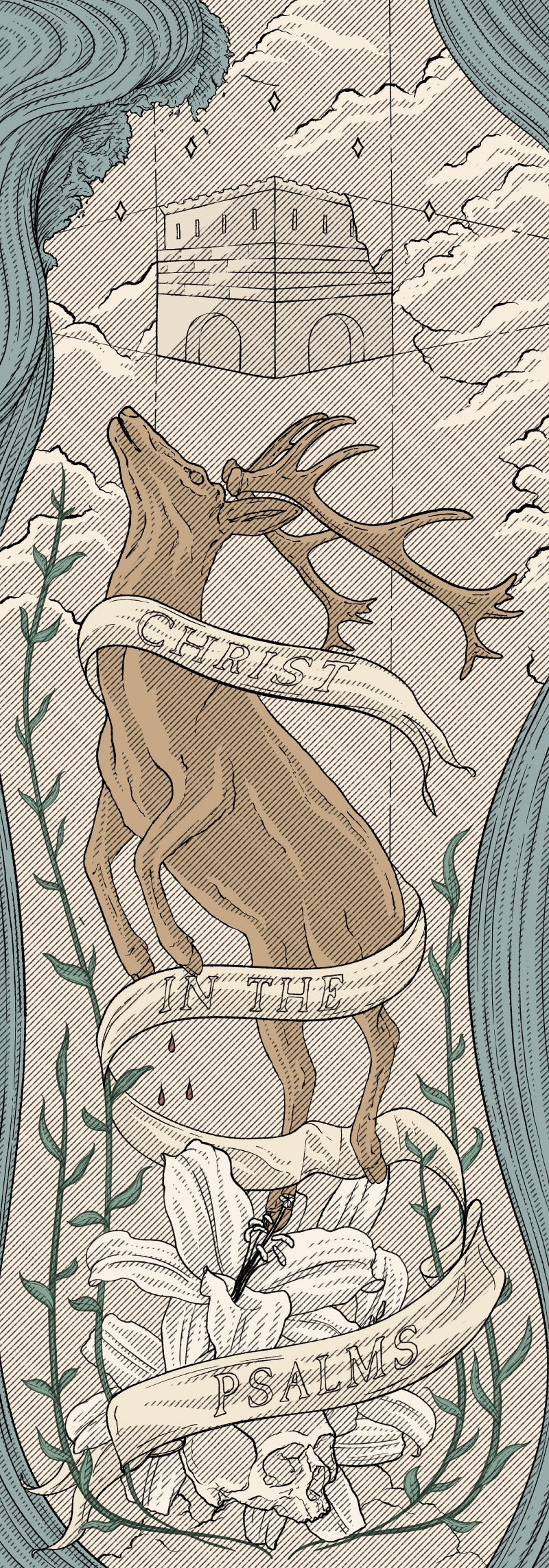

Behind the Art: Christ in the Psalms 2025

Written by the artist, Seth Coulter

Overview

I once heard that the Psalms engaged the full-stretch of what it meant to be human. That every emotion—every troubled tear, and every enraptured joy—was within the purview of this collection. At the time, I thought I understood what that meant. What I didn’t understand then was how far that stretch could go, and it was these ancient prayers that not only did the engaging, but a good measure of the stretching as well. They offered me that which I had not had the ability to articulate past a groan before. I found I had stored within my chest disquieted, dust-beset things—thinking them too unbecoming to offer to God—not knowing that they were in truth a lament or a jubilation shared by my brothers and sisters across the deep levels of time. I found I had been holding back whole stretches of myself—both desperations and passions. The Psalms revealed that these cries were indeed offer-able to God—that I was able to give all to Him—and to my surprise, in so doing, I found myself (with these Psalms in my mouth) weeping at the crowded space beneath the cross, rejoicing at the open tomb door. I was not alone in this. It was there in my weeping and rejoicing that I found a great collection of saints around me, gathered there as well. We were bound together in these prayers.

This thematic world lies at the heart of what I tried to construct for the Christ in the Psalms series artwork. The Psalms are the prayers of God’s people. As such they span time, space, interiority, and community. They are within us as they are with us. They bind us to a community within our age, and within ages upon ages. They, in essence, bind us to a bigger world.

“The Psalms, with a few exceptions, are not the voice of God addressing us. They are rather the voice of our own common humanity…about life the way it really is, for in those deeply human dimensions the same issues and possibilities persist. And so when we turn to the Psalms it means we enter into the midst of that voice of humanity and decide to take our stand with that voice. We are prepared to speak among them and with them and for them, to express our solidarity in this anguished, joyous human pilgrimage. We add a voice to the common elation, shared grief, and communal rage that besets us all.”

—Walter Brueggemann, Praying the Psalms

In this spirit of offering all (the full-stretch) through prayer to the God who would hear us, I decided to shape the banner-art around two overarching themes: Love and Suffering. These two categories (and the tension between them) uniquely seem to capture much of what humans face in the course of a life. I’ll say more about that quickly.

We desire to love and to love without end though we know in our bones that ends come: ends exist in a myriad of forms: the death of dreams, of relationships, of us. Death—as we think of it, would be the chiefest of all absurdities—it makes no sense to that which we in every way live for: love. Death is more than an inconvenience—it is confounding. It frustrates the very core of us despite its ubiquity. The Psalms do not shy away from any of this difficulty, and would teach us to pray through both of these major thoroughfares and into the smaller, quieter streets of the human emotional experience. To give voice to love, to suffering, and to the diapason between.

Even with the way the Psalms offer voice to our full stretch of love and suffering, we would still be left with a question—we would desire to ask the God we love, “what are you doing about this suffering? It is here that the Psalms do not stop, but go still further. The Psalms engage, stretch, and give voice to our love and suffering, but they do something more also—they point us to Christ. They point us to the Love that would seek to abolish suffering, even “unto death, even the death of the cross.

And so, the direction of our art is Love and Suffering, and it is there between the two that we find Christ. Christ in the Psalms.

Symbols

The above themes are expressed in the following ways:

Mingled Categories

It may be helpful to mention early that the banners themselves represent our arch-themes of “Love” (Left Banner) and “Suffering” (Right Banner). Though, the banners may (and should) be observed to be muddled: there are thorns on the left banner, and flowers also growing on the right. The Psalms present us with categories (ie: praise, lament, wisdom, imprecatory, etc.) but these are not clean categories. Likewise, these banners are not cleanly demarcated, as life is never wholly one thing or the other, but a complicated mix. The symbols, therefore, are mingled.

The Deer (or Stags)

A major symbolic device in this art are the deer. “As the deer longs for streams of water, so I long for you, O God.” This line from Psalm 42 gestures us towards the central point of the art, and I would argue the Psalter itself: we are creatures with longings, yet there is only One “place of water” where we might be truly refreshed. The Holy God Himself.

A major symbolic device in this art are the deer. “As the deer longs for streams of water, so I long for you, O God.” This line from Psalm 42 gestures us towards the central point of the art, and I would argue the Psalter itself: we are creatures with longings, yet there is only One “place of water” where we might be truly refreshed. The Holy God Himself.

Yet sometimes in life we face various seasons, some extremely difficult. The antlered deer on the left is in one season, while the one on the right—now losing its antlers—is in another. We may consider the antlers as raiment, glory, health, or many other things—and in so doing, consider them as something positive (or, even something we may mistakenly attribute too much hope to.) The deer (or stags), may represent humanity, while also representing the Second Adam: Christ. I include the term “stags” not as an embellishment, but to connect us to other symbols in the worldwide church. Christ has been historically represented as a stag in Christian art: the Celtic church during the medieval period is a good example. This Christological connection in our banners can also be seen with the deer on the right who is bleeding from the side, an echo of Christ’s spear-wound during the Passion.

Left Banner: Arrows, Shield, and Rain

Focusing on the left banner, the shield above the deer’s head connects to imagery found in Psalm 3:3 and Psalm 28:7: God acting as “refuge” and “protector,” and offering—as seen in Psalm 91—a “shadow” of “shelter.”

There are 6 arrows falling down onto the shield to represent the incompleteness or chaos that pushes in on our lived experience (the number 6 is a common symbol of incompleteness in Scripture). Yet instead of the arrows destroying the deer, the shield halts them. Under the shield fall 5 raindrops: 5 is a repeated number in these banners as there are 5 books in the Psalter. Rain itself symbolizes the care and restorative love of God as in Psalm 68:9, “You sent abundant rain, O God, to refresh the weary land.” God is our refuge and restorer.

Right Banner: Jerusalem, Lillies, and Blood

We now switch our attention to the images on the right banner. This banner contains allusions to Jerusalem—a city of imagery itself: both joyfully triumphant and hauntingly desolate. Our minds here oscillate between exile and restoration, Babylon and Thy Kingdom Come, and between Caesar’s Rome and The New City of Revelation 21.

We now switch our attention to the images on the right banner. This banner contains allusions to Jerusalem—a city of imagery itself: both joyfully triumphant and hauntingly desolate. Our minds here oscillate between exile and restoration, Babylon and Thy Kingdom Come, and between Caesar’s Rome and The New City of Revelation 21.

The deer on the right banner is bleeding from the side. Historically in Christian art, Christ’s spear-wound is always portrayed on His right side. Here, the wound’s bleeding falls upon a flower known as the Madonna Lilly that is native to the Jerusalem region. The blood keeps descending eventually to a skull. It is here in our banner’s symbolism that we see the blood of Christ being shed for the plight of humanity. The calamity which began in the Garden—seen vividly articulated through the laments and hopeful prayers of the Psalms—find restorative answer in the sacrifice and victory of Christ. In Christ now and in the Age to Come, is found the promised end to all calamities, “He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more.” The full stretch of the human experience is set within the eschatological hope that was instantiated on Good Friday and Easter.

If the Garden is represented in the lower section, Jerusalem is alluded to in the higher section, though the city is seen as being incomplete (as the Psalmists would have known it). And so using this Psalmic imagery, we hold onto the reality of things being difficult in life, sometimes extremely so, and yet we are given a promise of a “kingdom without end” coming as God fulfills what He promised He would do.

Banner Borders: Chaos Waters and New Growth

Lastly, we end with two contrasting images that sum up what we have been discussing. The right banner is bordered with chaos waters. Chaos pushes in on us even as we walk with the God who hears our prayers, and acts with and for us. The chaos waters, though, are not the only thing to notice here. We also notice new life: seen in the flowers at the bottom of the banner, but also in the new shoots and leaves rising around the deer. Love and suffering intermingle—the Psalms give utterance to our everyday life as we look forward to the time when there will indeed be “no more tears. Likewise, on the left banner we see thorns, but beauty also. The roses remind us of the goodness of God and our ability to enjoy sweet things, even in wild places.

Closing Remarks

It is my hope that these art pieces and their symbols may in some way act as a kind of imaginative catalyst. That they may bring some of the beautiful and challenging themes of the psalms to our minds visually. These art pieces are an attempt to capture something of the width and breadth of the Psalter. The Psalms are not prayers of the wishful-thinkers, but rather prayers that are truly sustenance and refreshment for those in the dust, in the grit of the everyday. Prayers for those seeking God and willing to wrestle with Him—wrestle with Him until dawn reveals a brand new day.